Waste hierarchy

How to Reduce Textile Waste

The waste hierarchy is a framework that helps us prioritize sustainable actions when it comes to textiles. It ranks different waste management strategies from most to least environmentally friendly. By following this approach, we can reduce waste, save resources, and lower our impact on the planet.

1. Prevention – Avoid Waste from the Start

The best way to deal with textile waste is to prevent it altogether. This means:

- Buying less and choosing better – Investing in durable, high-quality clothing reduces the need for frequent replacements.

- Opting for sustainable materials – Clothes made from organic, recycled, or biodegradable fibres have a lower environmental impact.

- Taking care of what we have – Washing clothes at lower temperatures, air drying, and repairing small damages can extend their lifespan.

2. Preparing for Re-Use – Give Clothes a Second Life

Before getting rid of textiles, consider whether they can be used again.

- Donate or sell clothes that are still in good condition.

- Swap with friends or participate in clothing exchanges.

- Repair and refurbish slightly worn-out clothing instead of replacing it.

3. Recycling – Turning Old into New

When clothing is no longer wearable, it can often be recycled.

- Textile recycling programs can process old clothes into new fabrics, insulation materials, or industrial rags.

- Innovative recycling projects, as displayed through the T-REX project, show that it is possible to recycle household textile waste into new fibres and garments. This is called fibre-to-fibre recycling and can be achieved using either mechanical or chemical recycling.

- Some brands and retailers accept old garments for recycling in exchange for store discounts.

4. Recovery – Extracting Value from Waste

If textiles cannot be reused or recycled, they can still be used for energy recovery.

- Some textiles are burned in waste-to-energy plants to generate electricity or heat.

- While not the best option, this prevents textiles from going to landfill and reduces reliance on fossil fuels.

5. Disposal – The Last Resort

Throwing textiles in the trash should only happen when no other options are available.

- Most textiles in landfills take years to break down, releasing harmful emissions and polluting the environment.

- Proper disposal means using designated textile collection points rather than putting clothes in the general waste bin.

By following this waste hierarchy, we can all play a part in reducing textile waste and making the fashion industry more sustainable. Small changes in our daily habits can have a big impact on the planet!

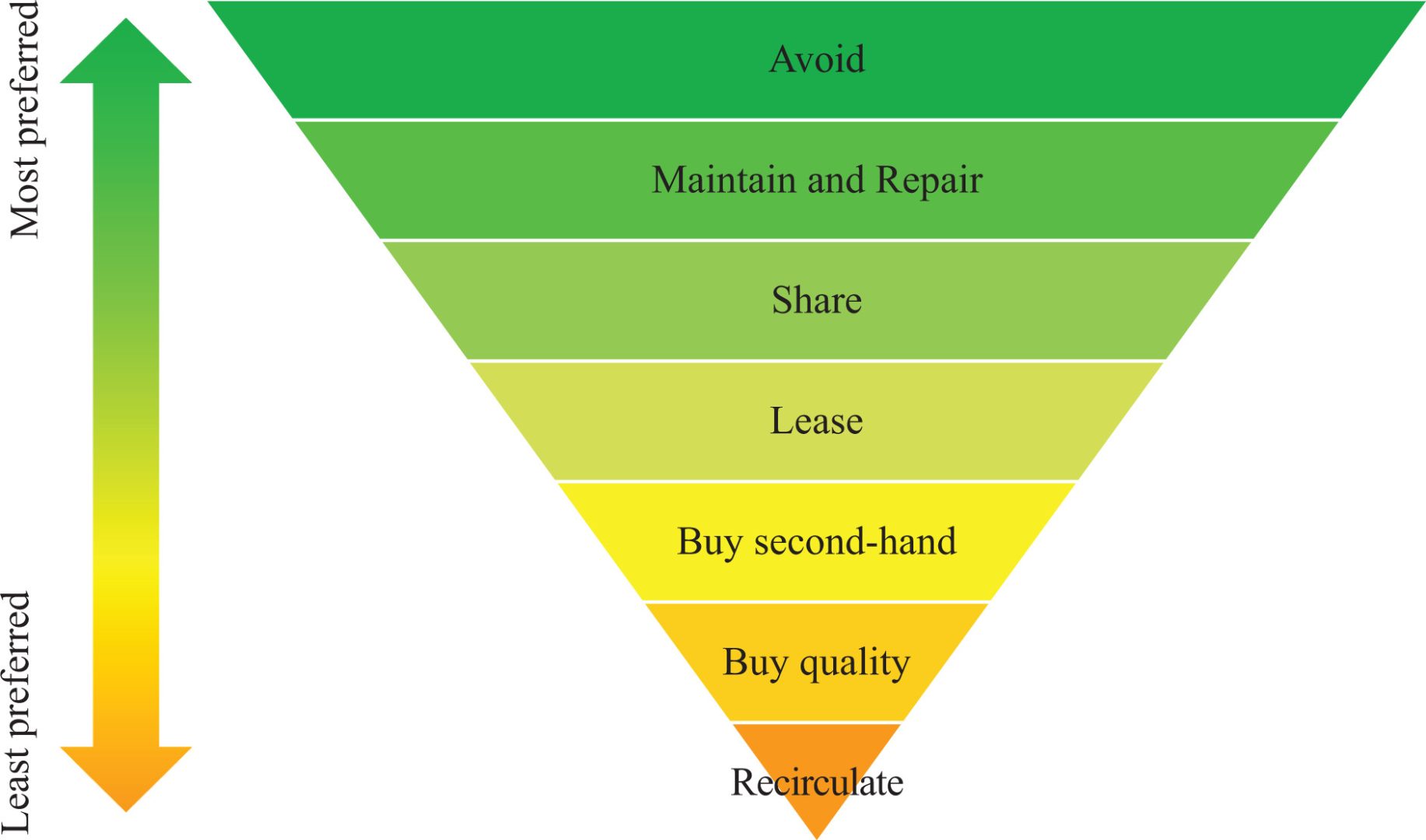

The Hierarchy of Consumption in a Circular Economy

While the waste hierarchy focuses on managing textile waste, a more sustainable approach is to rethink how we consume clothing in the first place. The Hierarchy of Consumption in a Circular Economy shifts attention to keeping textiles in use for as long as possible before they become waste. It ranks different consumption choices based on their environmental impact, encouraging us to move away from disposable fashion and toward long-lasting use.

1. Avoid – The Best Way to Reduce Impact

The most effective way to minimize textile waste is to avoid unnecessary purchases altogether. Fast fashion promotes overconsumption, but by making mindful choices, we can reduce demand and lower the overall environmental footprint of clothing production.

2. Maintain and Repair – Keeping Clothes in Use

Instead of discarding garments at the first sign of wear, maintaining and repairing them helps extend their lifespan. Simple actions like sewing a missing button, fixing a tear, or washing clothes with care can prevent premature disposal.

3. Share – Extending the Life of Clothing

If an item is no longer needed, passing it on to others can keep it in use. Swapping clothes with friends, participating in clothing exchange programs, or donating to second-hand shops are great ways to ensure garments find a new home.

4. Lease – An Alternative to Buying

Leasing allows consumers to access clothing without owning it. This is especially useful for special occasions, children’s clothing, or fashion-conscious individuals who want variety without excessive consumption. Renting clothes reduces demand for new production and promotes reuse.

5. Buy Second-Hand – Choosing Pre-Owned Over New

Buying second-hand clothing reduces the need for new production and gives garments a longer life cycle. Thrift stores, online resale platforms, and vintage shops provide stylish, affordable, and eco-friendly alternatives to buying new.

6. Buy Quality – Investing in Longevity

When new clothing is needed, choosing high-quality, durable pieces ensures they last longer. Well-made garments, produced ethically and with sustainable materials, are a better investment than cheap, short-lived fashion.

7. Recirculate – Keeping Textiles in the Loop

When clothes can no longer be used, they should be kept in circulation through recycling, upcycling, or repurposing. This prevents textiles from becoming waste and ensures materials are reused in new ways.

How This Complements the Waste Hierarchy

The Hierarchy of Consumption in a Circular Economy helps prevent textiles from becoming waste in the first place, while the Waste Hierarchy provides a framework for managing textiles once they are no longer usable. Together, they offer a comprehensive strategy for reducing fashion’s environmental impact:

- First, focus on responsible consumption—avoiding unnecessary purchases, maintaining clothing, and sharing or leasing items.

- Then, apply waste management principles—recycling, recovering materials, and ensuring proper disposal when textiles truly reach the end of their life.

By following both hierarchies, we can transition to a more sustainable and circular fashion system, where textiles are valued, waste is minimized, and resources are used responsibly.

1 Source: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/waste-framework-directive_en

2 Source: Maitre-Ekern, E., & Dalhammar, C. (2019). Towards a hierarchy of consumption behaviour in the circular economy. Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 26(3), 394-420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1023263X19840943